Contents

Introduction

First published in 1964, The Ladybird children’s book, The Story of Cricket, was, as it must have been for many boys, my first exposure to the history of the game. The Ladybird format was well established and very successful; a page of text would be faced by an illustration bringing the theme of the page to life. The pictures were lively and cheerful, and left the reader with a strong visual memory. Impressively, out of twenty three pairs of pages, no less than ten are devoted to the very early history of the game. Women’s cricket also gets a feature in relation to the modern game.

The stories told reflects the traditional understanding of the game’s history, however many of the episodes described have since been partially debunked and are sometimes regarded as outright myths. That however should not detract too much from an overall appreciation of an appealing and influential contribution to the literature of cricket.

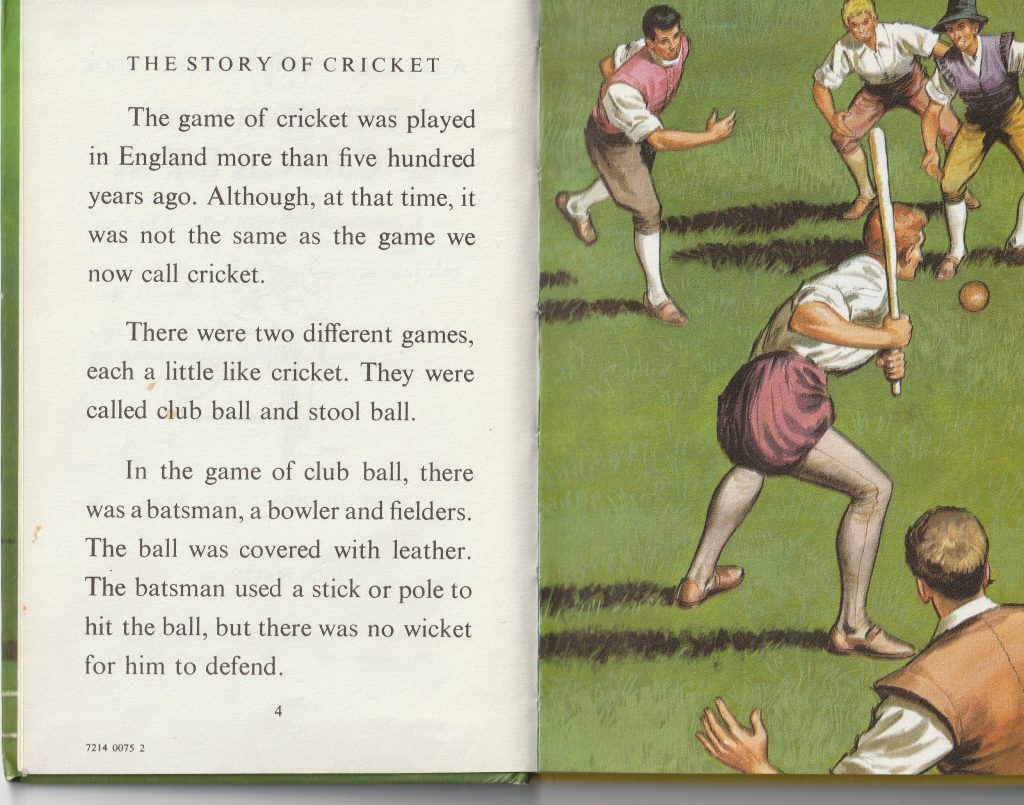

Club ball

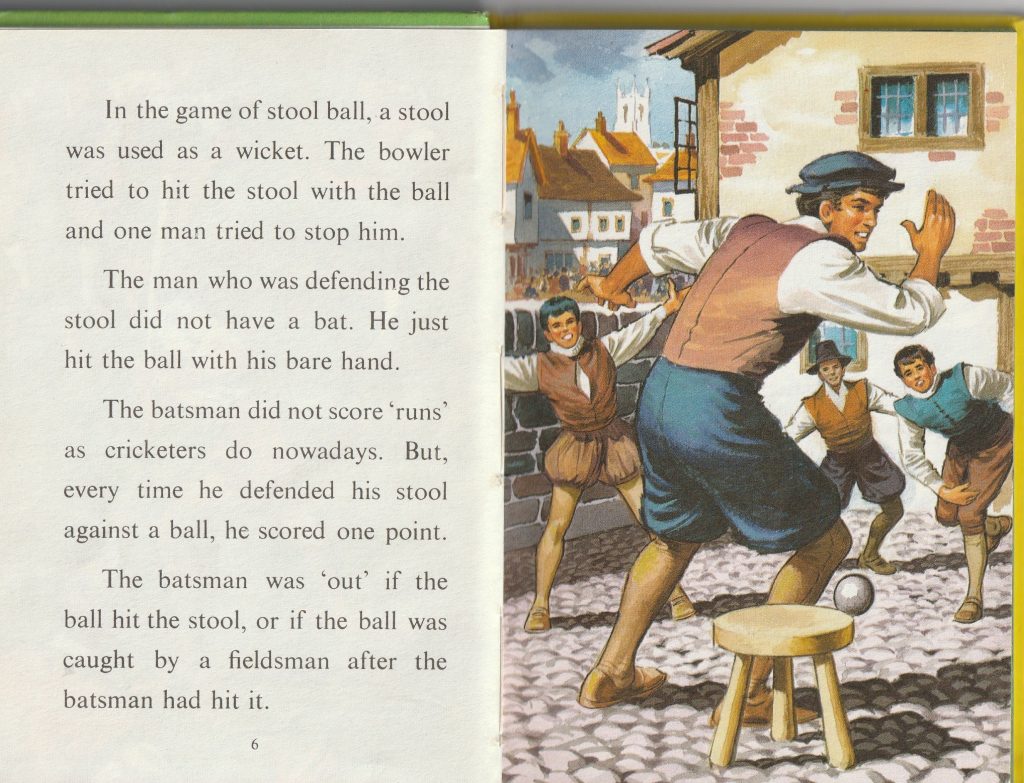

Stool ball

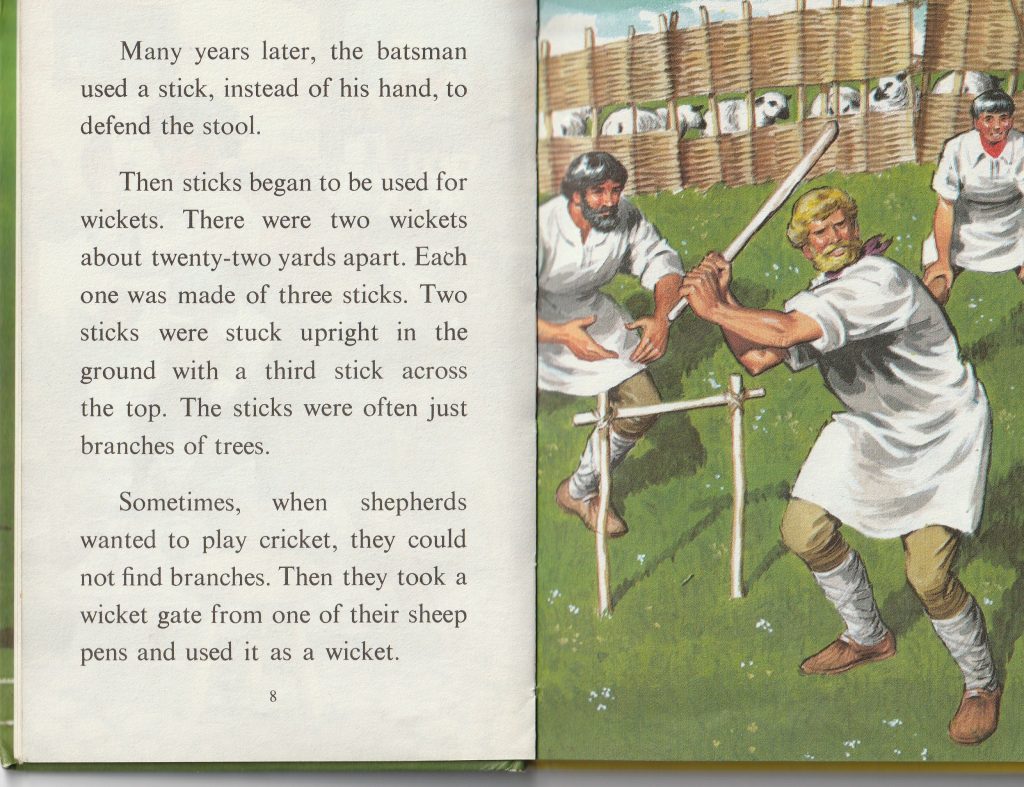

Shepherd’s role in the origin of cricket

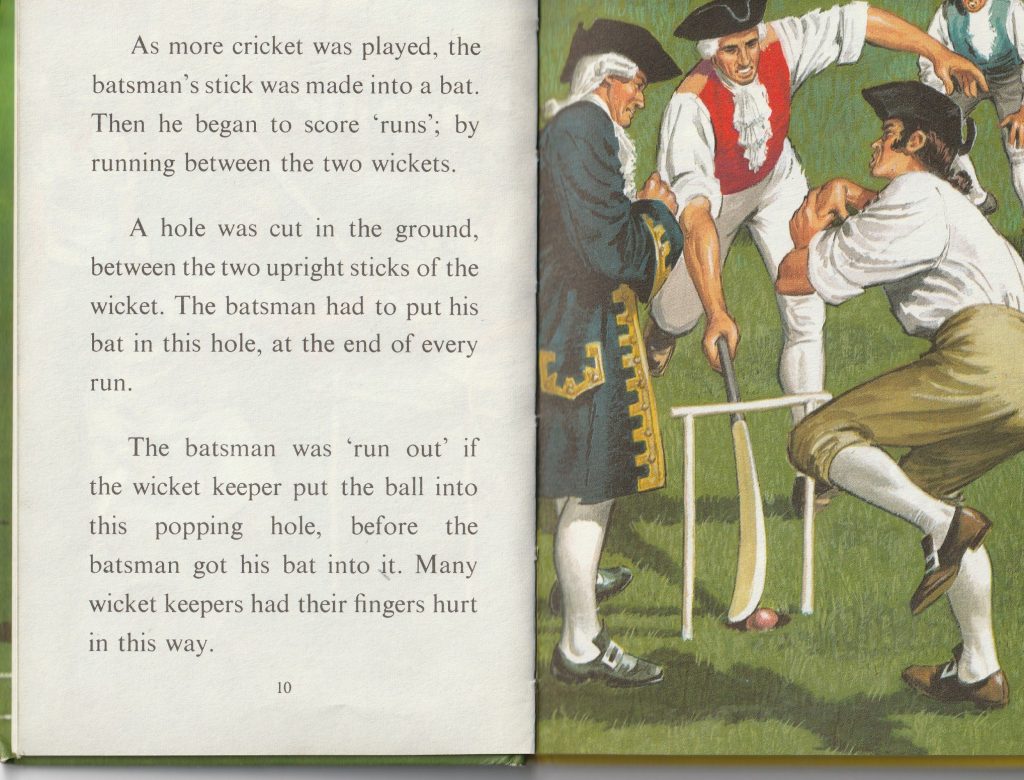

Hole in the ground run out law

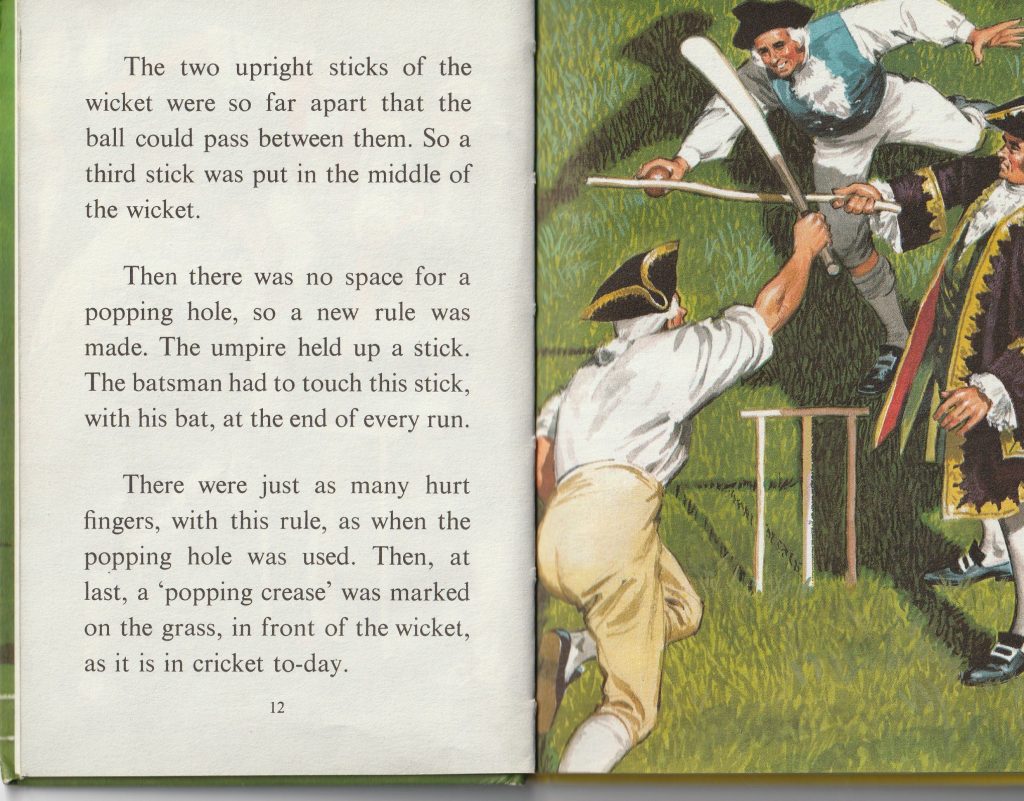

Umpires holding stick run out law

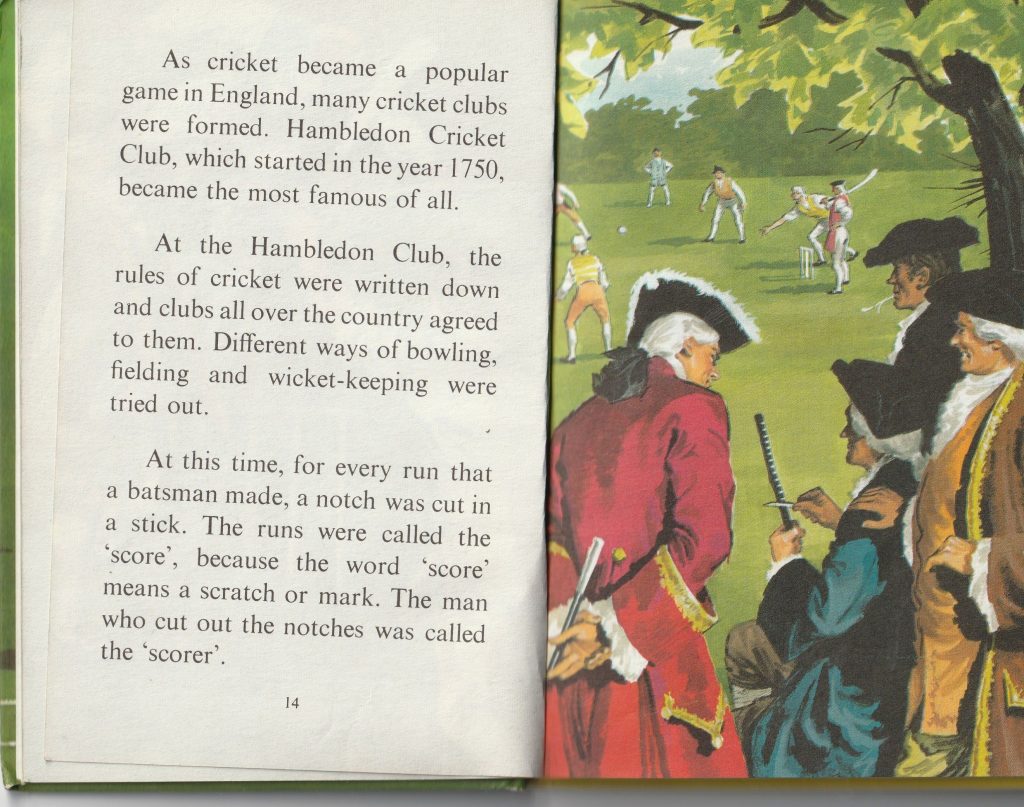

The Hambledon Club

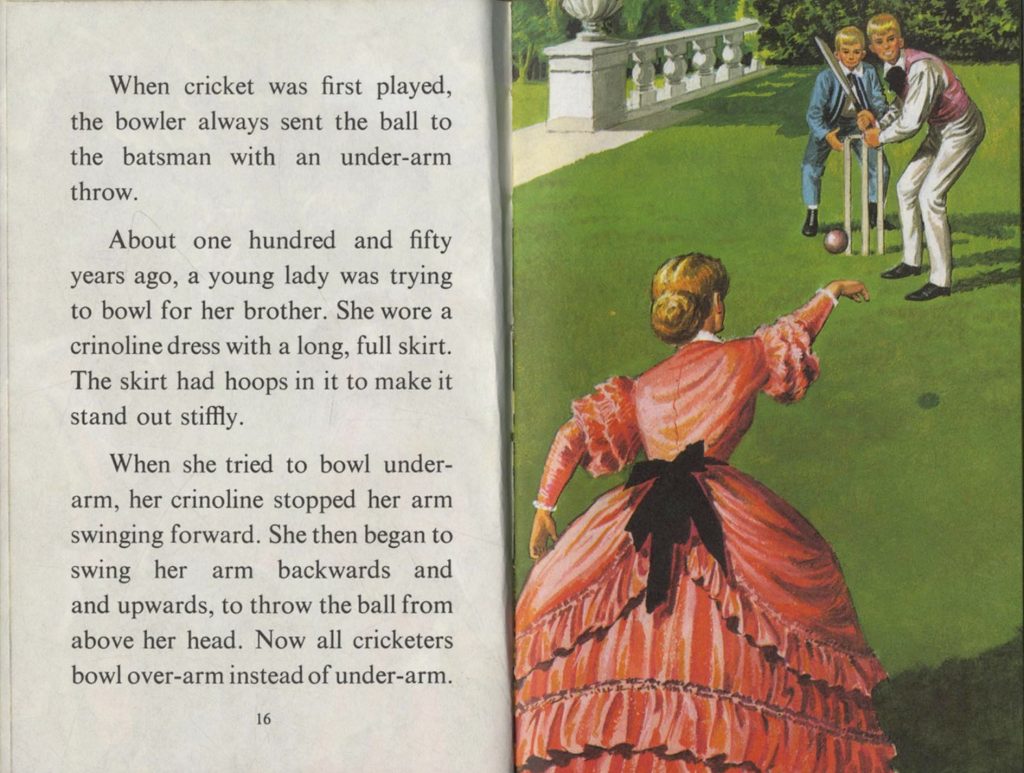

Christiana Willes and overarm bowling

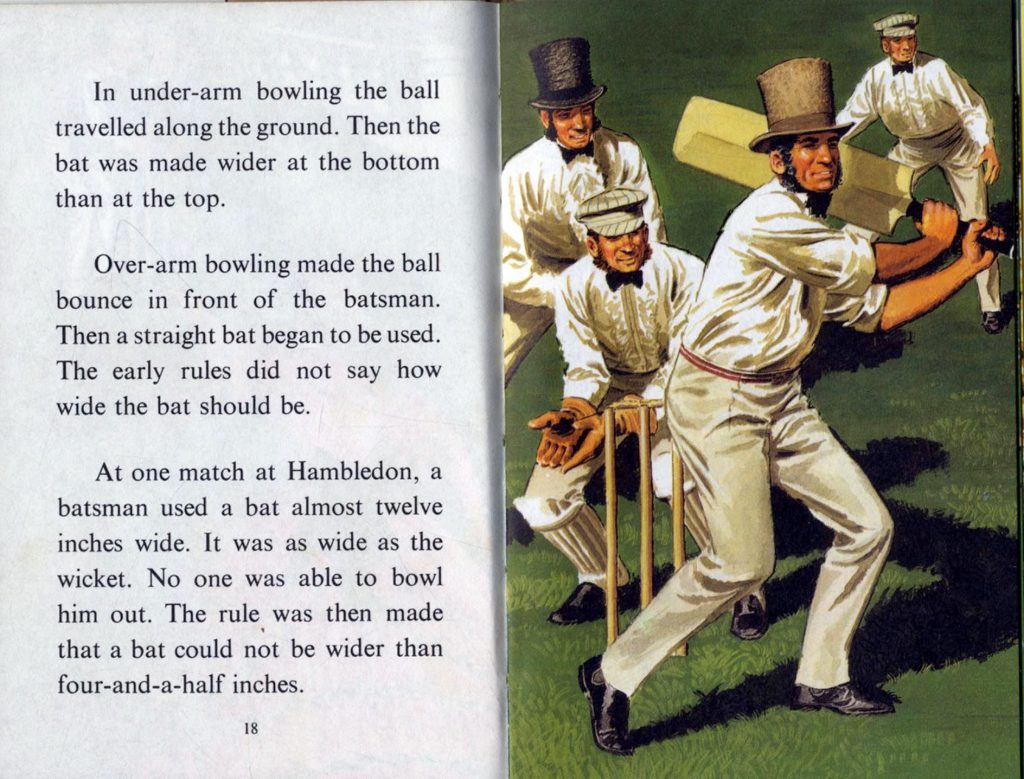

The large bat incident

The error is however, understandable. The change that that happened was that bowlers has started to bounce the ball before the batsmen and make it lift towards them while still bowling underarm, rather than rolling it along the ground – Lumpy Stevens of Kent and David Harris of Hambledon ware the main exponents of this type of bowling, which started to emerge in the 1760s. That is when bats changed from being shaped like a shoulderless club to the shape that is now familiar.

The incident illustrated comes from Nyren and the player is identified as Thomas White of Reigate, not someone else called Shock White as was once thought.

Note that the wide bat bat is shown with a cane handle, rather than a just one piece of wood – not quite right, as the spliced bat did not appear until well into the nineteenth century. Overall, the illustration is a later period than when it actually took place, for instance white clothing was not yet de rigueur and it was still the two-stump era (the incident that brought towards an end took place in 1776), pads didn’t come in until after 1800. But I do love the headgear and the side-whiskers, not to mention the bow-ties.

I can’t resist this little aside. On 8 July 1976, John Edrich and Brian Close, both survivors from another age, opened the batting against the West Indies at Old Trafford and, to say the least, struggled against extremely fast short-pitched bowling. In the second innings, Close (wearing what looked like an office shirt) made 20 off 108 balls and got hit about 20 times.

A not-so-kindly spectator ran out onto the field and gave Edrich a wider bat, perhaps even inspired by memories of the Ladybird illustration.

Neither Close not Edrich ever played for England again. Two fine players, among the best cricketers of their era. My father was a great fan of John Edrich – and they died on the same day – 23 December 2020. RIP.

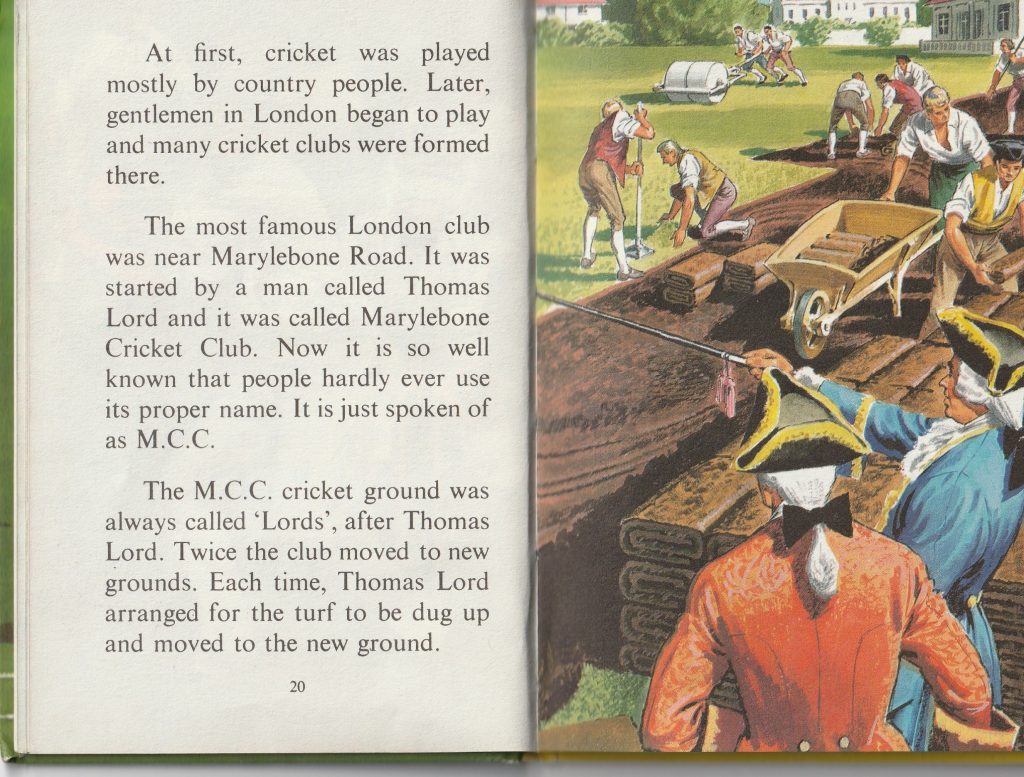

MCC and the Lord’s Cricket Grounds

On another point – look at the flat-based implement being used on the edge of the grassed area; implements like this are still seen in action at cricket grounds to-day, used to flatten out bowlers’ foot-marks. Sometimes called a thumper.

Strange though, that a pavilion is in place before the grass was laid…

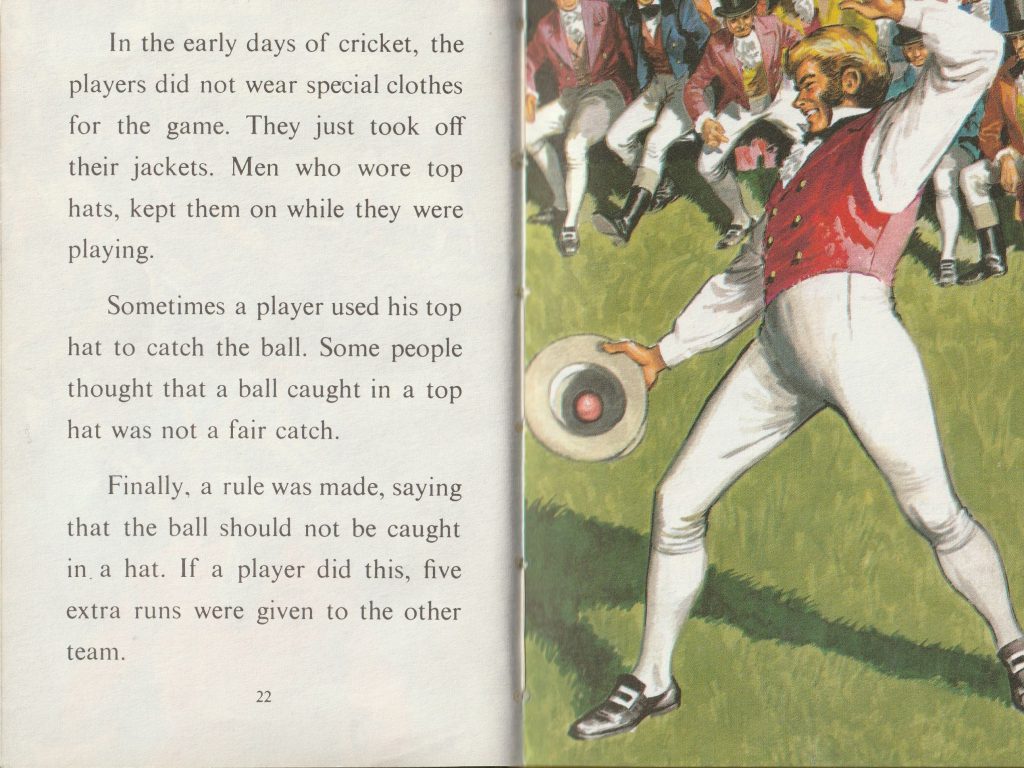

The penalty runs law

Am I right in seeing a similarity to this caricature, produced by Charles Crombie in 1906?

Recognition of the Ladybird book

The book’s importance was recognised by MCC in 2015 when it was the subject of an exhibition on the Lord’s Museum.