Contents

Bats

General

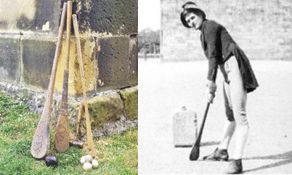

This illustration of the evolution of the cricket bat is based on one that first appeared in the 1871 book, Echos From Old Cricket Fields by Fredrick Gale, albeit with the hockey stick style bat added. Note, none of the bats are spliced.

Approximate dates are:

1 – Hockey style -1720

2 – Shoulderless – 1750

3-5 – Modern design 1774, 1792,1793

Bur first a puzzle. John Nyren (1764 – 1837) described the bat of 1746 as being ‘like a dinner knife, curved at the back and sweeping in the form of a volute at the front and end‘. A volute is spiral, scroll-like ornament that forms the basis of the Ionic order, found in the capital of the Ionic column. I don’t think this is much a a description of any of the bats discussed below. What did he mean? I think he is describing the shoulderless bat as being like a dinner knife – but the volute?

Perhaps as well to remember that John was not born at the time and his father was himself only ten years of age.

Archaic bats

Stonyhurst bats

One obscure aspect of cricket history, often ignored in the of the the narratives of the history of the game is the version of the game once played at Stoneyhurst College, a Catholic boarding school in Lancashire. In 1593 the Jesuit, Fr Robert Persons, set up a school in St Omers in France for the education of English Catholics who were unable to receive such an education in Elizabethan England. The College of St Omers operated until 1762 when, forced to leave what was by that time part of France, it moved first to Bruges, then, Liege (1773) and finally to the supportive and out of the way Stonyhurst estate in Lancashire (1794).

The school boys and their teachers who returned to England brought with them their own games including that of cricket. But it was a form of the game preserved by geographical and cultural distance from the evolution of the game in England. It was a form of the game probably dating back as far as the College’s foundation in 1593, if not beyond. This was believed to be similar to cricket played in the villages at the time of Cromwell’s Commonwealth. So it was preserved in a kind of time-warp and carried on being played until the second half of the nineteenth century.

Three bats, some leather balls, a stone wicket and a mallet survive. The bats are, three feet in length tapering to an oval head 4½ inches in width and were made by villagers in the winter months. They either consisted entirely of ash, or had an alder-head spliced on to an ash-handle.

There are two other clues which make we wonder if these implements were once in widespread use.

First, we have one of the very earliest mentions of the word ‘cricket’. It occurs in the 1611 publication A Dictionary of the French and English Tongues by Randle Cotgrave. He defines ‘crosse’ as being ‘A crosier, or Bishop’s staffe; also a Cricket-staffe; or, the crooked staffe wherewith boyes play at cricket.’

This creates the idea of a circular end to the bat, not a right angle.

So – I am suggesting, maybe before the hockey style stick, there was a round ended bat used perhaps in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. I doubt if anyone will prove me wrong as there is really no way of knowing.

The hockey-style bat

One thing about early cricket that most enthusiasts know is that the first bats were shaped like a hockey stick. This indeed is apparent from many of the paintings of Eighteenth Century cricket.

For example, the painting below, wrongly known as, Cricket at the Artillery Ground is based on an engraving of 1743 which itself was based on a now lost painting of around 1735 (left). The reasons for this shape of bat widely understood to be as follows. Until around 1760, balls were delivered rolled along the ground – the contact point would therefore always be on the ground itself, so that is where the bat needed to be broadest. It is suggested that they survived to the until the idea of pitched, and therefore bouncing, deliveries took hold. I do note however, that Gale’s illustration above does not include one resembling a hockey stick, so it would seem, not many of these survived into the mid-Nineteenth Century when he was building his collection. At all events, as far as I am aware there are only three known examples of hockey stick bats that are around today. And these are shown below.

This bat , 1729, is on display in the Sandham Room at the Oval, London, home of Surrey CCC. It originally belonged to John Chitty of Knapshill.

To the left, this bat, possibly dated around 1720, is on loan to the Lord’s museum. It was discovered behind a fireplace at Boredam Hall, Kent. In truth, it is a strange shape, the toe is not really square enough to the shaft to make it much use against the rolled ball. But – it conforms very closely to the bat illustrated in the 1735 picture above.

This bat which recently came to auction (realised £10,000) was once owned by Breaston CC, Derbyshire, and was on at some time on display in the pavilion in the Soldier and Sailor Sports Ground.

It’s weight is 3lbs and at its widest point it is 4” wide. It has evidence of use to hammer in stumps. The only suggestion of age given in the auction listing was ‘Eighteenth Century’.

Not a bat, obviously, but a similar instrument – a fulling club, a tool of medieval wool-making, here illustrated in the hands of an apostle at Fairford Church, Gloucestershire, dated around 1500. Could there be a connection to the early cricket bat? I ask, is the implement discovered at Boredam Hall, not a cricket bat but a fulling club? We will probably never know.

I have given some thought to the question, rarely asked, of how these bats could be effective. Of the three surviving examples, only the Breaston one has a toe end anything like at right angles to the main stick and easily wins the best-in-show award. The Sandham room one has a toe at 45 degrees and the Boredam Hall one is nearly straight. If a ball was genuinely rolled along the ground, as is commonly believed, the first two would be of little more use than a straight stick. So – I would offer the following as possible explanations.

- I do not think the ball was not rolled, even early on in the game’s history. This would have been hard as grass was not cut mechanically, any pace would have been lost by the time it reached the striker. Rather it was skimed so as to bounce two or three times, so that batsmen would typically strike it while it was slightly off the ground. To support this, look at the image above where you can see the artist is at trouble to show ball casting a shadow a little way away – why do this if not to show it off the ground.

- To add to this point, the catching mode of dismissal was, as far as we know, an original feature of the game. How would this work if the ball was always on the ground? In particular, the first attempt at a code of rules that we have specifies that catches behind the wicket count – all but impossible for a genuinely rolled ball.

- I tentatively suggest that the hockey-style bat was adopted early as these were used in other games and pastimes, as suggested by several of the very early images. Or even – as we see above – a fulling club.

- The basic batting technique would involve backing off the on side and seeking to make contact with the ball, with the bat at an angle of something between 45° and 60°. This would have had the effect of bringing the head of the bat something more like parallel to the ground and give the striker a better chance. It would also mean that the ball would generally go on the off side, something supported by the predominately off-side fields seen in most cricket paintings – mostly 7-2.

- Another tentative suggestion I am prepared to make is that sometime around 1740, dissatisfaction grew with the hockey-style bat as it was not as effective as batsmen wanted. So the shoulderless bat was designed, a stronger implement, which would offer more power, better balance and, I speculate, less likely to break. It would also give the batsmen the chance to pay with a somewhat straighter bat. That is not to say that the shoulderless bat took over immediately, mass advertising was not available. Rather it would have been phased in, and soon became a fashionable product; several family portraits of youths showing off such items indicate that it was a prestigious piece of kit.

So let us consider it in more detail.

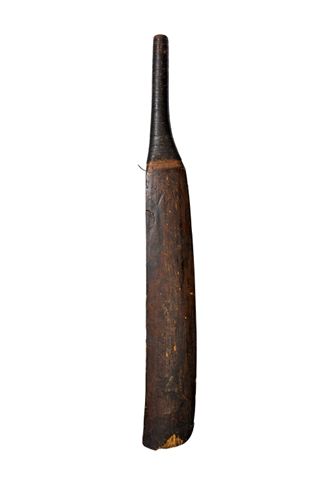

The shoulderless bat

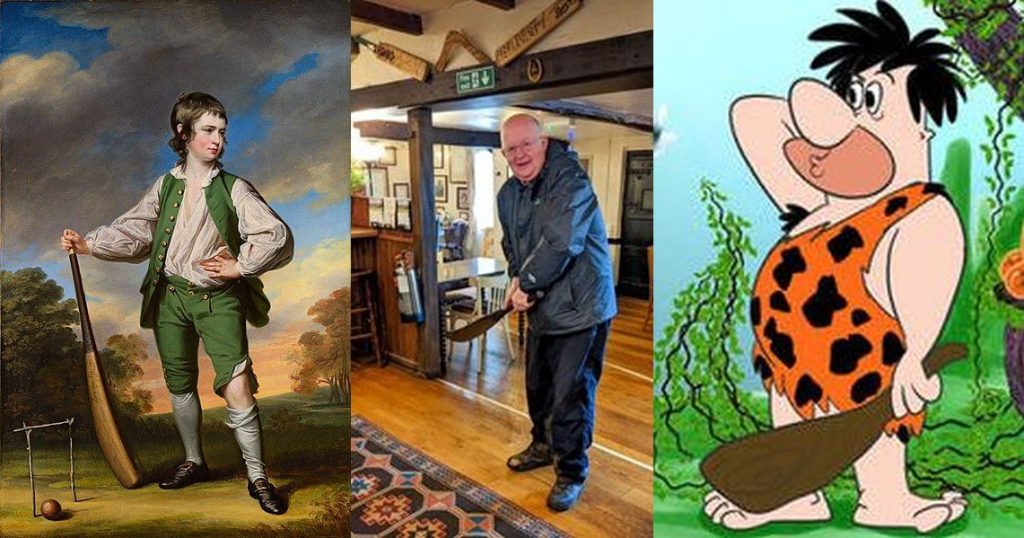

This bat looks a bit strange to the modern eye – is something like the type of club the stone-age cartoon figure, Fred Flintstone, might be seen with. Rather more delicately John Nyren describes a 1746 bat as being” similar to an old-fashioned dinner knife – curved at the back, and sweeping in the form of a volute [scroll-like ornament] at the front and end”. There are a few of these bats still around and several photographs as well, and they all seem conform closely to a pattern. A strapped handle, broadening out gradually to the striking face which is very thick and curved, especially down one side. There is no particular strengthening in the toe, but the whole thing is very solid.

My view is that these were still designed to be used for facing a skimming ball, and for off side play with an angled bat, deployed by a batsman rooted on the leg side of the stumps.

Three shoulderless bats held by the MCC museum. All believed to be circa 1750. They are certainly asymetrical and some curve more than others, but beyond issue, none can be described as shaped like a hockey stick. Yet writers (eg see Cardus below) still stay with the simple story that the hockey-style bat was the one that preceded the modern shape, even when confronted with numerous bats of the style shown above. Well, gentle reader, we know better, don’t we.

Three exponents of the shoulderless bat – Lewis Cage, 1768, Francis Cotes; me, at the Bat and Ball Inn, Hambledon (believed replica bat); and Fred Flintstone.

Modern design

It is sometimes said that the man responsible from introducing the square shouldered bat in the 1760s was the great player, John Small of Hambledon. It is more accurate to say that he was the first batsman to master the use of the straight bat and that he subsequently manufactured them in his workshop.

The transition though from the shoulderless bat to the shape we recognise today was undoubtedly the result of the development of the length ball, associated chiefly with David Harris, in the 1770s. The great Cricket writer, Neville Cardus wrote in 1945 : “As soon as the Hambledon men bowled a length and used the air and caused the ball to rise sharply from the ground, a hockey stick sort of defence was of no avail, so the shouldered narrow blade was evolved”. Of course, Cardus, like many writers, seemed unaware that long before the introduction of the length ball the shoulderless bat had replaced the hockey stick style, but there is still much in what he says. The length delivery meant that it was the upper reaches of the bat that was important, not the toe, so a different style of bat was essential.

While the shape became recognisably modern the manufacture of the bats was not. As Hugh Barty-King says in his fine book about the history of cricket equipment, Quilt Winders and Pod Shavers “the solid wood, one piece ‘plain match’ implement was the only kind of bat well into the nineteenth century. So, spliced bats, cane handles and springing were unknown in the period covered by this website.

Here is a selection of bats owned by MCC.

This bat is largely in the modern style, but is still asymmetrical, so can be seen as an intermediate one between the shoulderless bat and the modern bat. MCC dates this bat around 1770, but Barty-King dates a similar one, owned by the Vine Cricket Club as being c1755 and made by William Pett, the dates being supported by details of the purchase (4s 6d). This style though took many years to win through.

From the MCC collection, around 1790, used by John Ring. It is inscribed ‘Little Joey‘. The museum says it has a worn inside edge, but I am not sure that is right, it looks to me as if it is just shaped that way, perhaps reflecting an established tendency to back away to the leg side, present the bat at an angle, maybe with the toe trailing on the ground and aim for the off side.

1790, a bat owned by Robert Robinson.

Unique modification with tapered section in the centre of the handle, and asymmetrical shoulders. This appears to be a very early example of a modification for a disabled cricketer. Left-handed Robinson was, according to John Nyren, one of Hambledon’s most eminent players. The bat has uneven shoulders and also a specially turned handle with a tapered section in the centre. This alteration is presumed to accommodate Robinson’s left hand, missing two fingers following a childhood accident.

Bat of E Bagot, 1793. Typical of the evolved bat of the eighteenth century.

It was around this time that details of the first bat manufacturers began to appear. John Small is mentioned above, so is William Pett of Sevenoaks. Charles Budd of Brighton is another name I have come across. Before that, it may be presumed, players were responsible for either making their own bats or commissioning a local woodworker to do it for them. A variation could be that teams had earlier developed a skilled bat-maker who could be persuaded to make bats for players of local clubs.

Another issue is materials. I can find no great evidence on this and personally, lack the skill to judge which wood is used in the bats I have seen. My guess is that a variety of woods were tried, perhaps though the bats that are around today are made of willow as that is known to be durable against the cricket ball.

As far as I can judge, the few bats I have handled seem of similar weight to today’s bats – perhaps two and a half pounds. Fredrick Gale records that one bat in his collection is five pounds, an astonishing weight, and, I would have think, virtually unusable.

Other Equipment

Balls

Balls have survived history much less well than bats, so it is harder to say very much about them. The MCC Museum for instance, has no balls from the Eighteenth Century, neither do they know of where any are to be found. Further more, As Barty-King says an air of mystery and sophistication enveloped the skill of making cricket balls, based, to some extent, of the lack of ready information as to how it was done. Unlike cricket bats, which anyone with woodworking skills could attempt, balls were the preserve of specialists, perhaps local cobblers were enlisted in the early days. By the end of the Eighteenth Century, there were three – Duke, Small and Martin.

We do have an account of how Duke went about this, quoted by Barty-King: “The Great secret is to wind the thread around an octagonal piece of cork, which forms the kernal of the ball… When the ball is perfectly formed with cork and thread, he delivers to men in a room adjoining and they put on the leather cover which is made on ball hide.” It sounds like the modern ball – I remember in my youth that a real cricket ball, rarer than now, was described as a ‘corky’.

As for the colour red – the first mention I have found of this is is 1843, in Dickens’ novel, Martin Chuzzlewit. He describes some ledgers as having ‘red backs, like strong cricket balls, beaten flat’. Another point is that Stonyhurst do have a leather ball to go with their amazing bats, but information is scare on this aspect of cricket history.

Protective equipment

By and large, protective equipment was not a feature of the game in the period covered by this site, reinforced gloves and protectors were not in use. There is however some small question about leg guards. Certainly there is no evidence in cricket paintings of the use of pads. Some sources connect the introduction of the LBW law in 1774 as evidence that batsmen were deflecting the ball away with that rudimentary bating pads and say that simple leather shin-pads, strapped under their breeches, were in use by batsmen. I am not sure though that this was the case;; a few batsman may have been kicking the ball away with their boots, and in any event, no LBW is recorded as being awarded until 1795. Also, I am not aware of any leg protectors have survived, though that, in itself, is perhaps not significant.

More significant though is Fredrick Gale’s conversation with old Surrey cricketer John Bowyer in 1871, whose recollections were of the early nineteenth century – in this conversation Bowyer said ‘It was no joke to play without pads and gloves on a bumpy down against quick bowling’. Similarly, in 1886, Rev. James Pycroft writes in Oxford Memories: a Retrospect After Fifty Years, Vol. 2: “When Lord Frederick Beauclerk [1773 – 1850] first saw leggings he never imagined they should be allowed in a match — ‘so unfair to the bowler.’” While that seems clear enough to me, it is still just possible that some players used unobtrusive protection, but I doubt if this was widespread.

Clothing

The evolution of cricket dress is a complex matter, it was only in the second half of the nineteenth century that all white clothing was absolutely settled on as the universal dress. That lasted about 100 years before the Packer revolution in Australia introduced new ideas.

For the concluding years of the Eighteenth century, our best guide is probably is the recollections of John Bowyer (mentioned above). He said that players dress was generally nankeen [pale yellowish cotton], silk stockings (which were often provided by patrons who supported the game), with a pair of socks pulled on over them and rolled over the ankle, laced boots, with sparrowbills [small rough nails], white shirts and hats. So it would seem there was a bias towards near-white clothing, even if this was not enforced in any way.

To some extent, this is supported by an examination of the many pictures of games of cricket. A Cricket Match at Mary-le-bone Fields (above) for example shows white as the predominate colour as early as 1740. Meanwhile An Exact Representation of the Game of Cricket shows white shirts with breeches in a variety of colours. Many other pictures show that white commonly features in cricketers dress though subject to many variations. An obvious example towards the end of the century is Cricket Match At Lord’s Ground In Dorset Square (1790) where clothing is virtually all white (or off-white). Similarly, Cricket at Mousely Hurst is all white.

Another important source of information is the 1744 poem, by James Love, Cricket, An Heroic Poem. In book II he writes

The Stumps are pitch'd. Each Heroe now is seen,

Springs o'er the Fence, and bounds along the Green

In decent White, most gracefully array'd,

Each strong-built Limb in all its Pride display'd.

This reinforces the idea that white clothing was always popular on the cricket field. It was not settled though as shown by the 1824 picture however, The Cricket Match, which shows a much more variable range of clothing. So perhaps a fin de siècle fashion towards white clothing was dying away.

Overall though, I think we can say that white was always main colour for cricket attire, but was by no means universal and was certainly subject to variations both locally and over time.