Contents

General

Other than this page, this site is about men’s cricket. That is largely because nearly all of the literature and other sources of information, such as paintings and poems, relate to the game as played by men. This page is an attempt to adjust the balance, even if only a little. Sadly, there are few books that touch on the subject and no collections of scorecards. There are also PhD thesis available on-line which make reference to the topic (for example: A History of English Women’s Cricket, 1880-1939 : Judy Threlfall-Sykes) Researchers have traced newspaper reports which offer a tantalising glimpse into an aspect of cricket which has largely been overlooked and forgotten. For instance, one report in 1756 states that cricketers Sarah Chase and Mary Coote were “the two most famous Women in the Kingdom”. I have not however been able to find out anything substantial about them.

We do know however, that women have been playing cricket during adulthood since the mid-eighteenth century. Women’s cricket has taken many different forms throughout its history, depending on who was playing and why the game was organised. The oldest form of cricket though was village cricket and the first recorded instance of a women’s cricket match appears to have been an inter-village game played on 26th July 1745. The Reading Mercury reported, “The greatest cricket match that ever was played in the South Part of England was on Friday, the 26th of last month, on Gosden Common, near Guildford, in Surrey, between eleven maids of Bramley and eleven maids of Hambledon [Surrey, not Hampshire], dressed all in white, the Bramley maids had blue ribbons and the Hambledon maids red ribbons on their heads. The Bramley girls got 119 notches and the Hambledon girls 127. There was of both sexes the greatest number that ever was seen on such as occasion. The girls bowled, batted, ran and catched [sic] as well as any men could do in that game.” The account was also published by the Stamford Mercury, Derby Mercury, Weekly Worcester Journal and other newspapers between 9 August and 16 August. A return match was scheduled to be played on Tuesday August 6th, although no report has been found to confirm it took place.

In 1747, George Smith, the leaseholder of the Honourable Artillery Ground in Finsbury, organised a two day tournament between the women of Charlton in Sussex against the women of West Dean and Chilgrove. Smith arranged for the transport of the players to the ground, which cost him £80. The ground was renowned for attracting a socially superior crowd who were attracted primarily to the high stakes gambled and privacy offered.

Throughout the second half of the eighteenth century women’s inter-village cricket matches were played regularly in the South East of England. In particular, inter-village cricket matches in Sussex, Hampshire and Surrey became a regular feature of rural festivities. There are accounts of fete matches at places such as Upham, Harting, Rogate, Moulsey Hurst, Felley Green near Cobham and Bury Common. Tournaments were soon organised, encompassing several matches over a two day period. It is clear that these matches were very popular with spectators as in 1768, a tournament of three matches was organised in Sussex. According to the press, the third match attracted nearly 3,000 spectators. One of the umpires, a principal in the Hambledon Club, was reportedly ‘so delighted with their activity that he made them a very genteel offer if they would play in Broad-Halfpenny Common, which they likewise agreed to’.

Traditional village fetes took place annually around the farming and harvesting schedule with the entire village participating in various activities that included sports, animal baiting, eating and drinking. Our knowledge of women’s cricket played at inter-village level and at feast occasions is limited. This is due to the slow growth of local papers, which in later decades prove invaluable to providing an insight into village activities.

However, the limited information available through contemporary magazines and newspapers indicates that participants were of the lower classes. A popular structure to the games was married versus single. It is important to note that the division of players by marital status was not reserved for women; men’s games in feast settings were similarly divided. The differentiation between married and unmarried was an important feature of rural society. Games were an opportunity for single members of the community to impress members of the opposite sex in their quest for marriage. Sporting prowess was a method of drawing positive attention to oneself for prospective life partners. As one anonymous observer noted, ‘nothing is more usual than for a nimble-footed wench to get a husband at the same time as she wins a smock’. Although the occasion was steeped in frivolity, it is clear that some of the women took the game seriously and were intent on winning. At a game between ‘XI Maids of Surrey and XI Married Ladies of Surrey’ at Felly Green on 11 July, 1788 Miss S. Norcross scored 107, which is the first known century by a woman. Victors were also awarded prizes, similar to the prizes awarded to women who won races during festivity days. Typically these were more homely than monetary, with plum-cakes, ale, lace, gloves or spoons being awarded.

As early as 1773, there is evidence that some women cricketers recognised their own potential to make money. In Bury, trial matches were held for the selection of a representative Bury team to challenge an All England women’s team. It was reported, ‘so famous are the Bury women at a cricket match that they offer to play against an eleven in any village in their own county for any sum’.

Similarly, in 1775 six single women beat six married at Moulsey Hurst by seventeen runs, where ‘many London gentlemen were present and there were great bets depending’. In 1777 a match was played in Wiltshire, for £50 and a barrel of ale, between eleven married and eleven maiden women.

At every level, the women cricketers attracted large crowds who admired their skill and athleticism. In 1792, the players in a match between Rotherby and Hoby, two hamlets in Leicestershire, were said to have performed “astonishing feats of skill and agility”, and after the match, the bowlers of the winning side were “immediately placed in a sort of triumphal car, preceded by music and flying streamers, and this conducted home by the youths of Rotherby, amidst the acclamation of a numerous group of pleased spectators.”

Upper-class women too played cricket, albeit away from any spectators in private country houses. The first known instance of an upper-class, private, women’s cricket game was reported in the Lady’s and Gentleman’s Magazine, published in September 1777. The magazine contained an account and engraving of the match ‘played at Seven Oaks by the Countess of Derby and other Ladies of Quality’ (below). The Countess was clearly surprised that her match had become public knowledge, responding to a gentlemen’s comment on her batting style with the shocked statement, “In the name of wonder….how came you know anything of my cricket-match”? This match is of particular importance, not only for being the first of its kind, but for its romantic sub-plot. It was reported that during the cricket match the eighth Duke of Hamilton fell in love with Miss Elizabeth Ann Burrell due to her cricketing skills. Incidentally, her brother Peter was been one of the leading cricketers of the White Conduit Cricket Club. The Newcastle Courant reported, ‘when she took the bat in her hand, then her Diana-like air, communicated irresistible impression. She got more notches in the 1st and 2nd innings than any lady in the game’. They were married before the start of the coming cricket season. This encounter promoted the concept that not all women who engaged in physical activity were unfeminine and repelled the opposite sex, even suggesting that their ability may be an added attraction.

A 1779 cricket match played by the Countess of Derby, formerly Anne Burrell. Apart from anything else, it is a good illustration of the early bowling action.

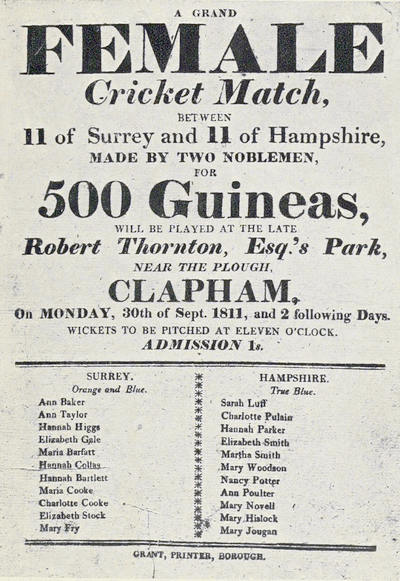

1811 – The first Women’s County Match

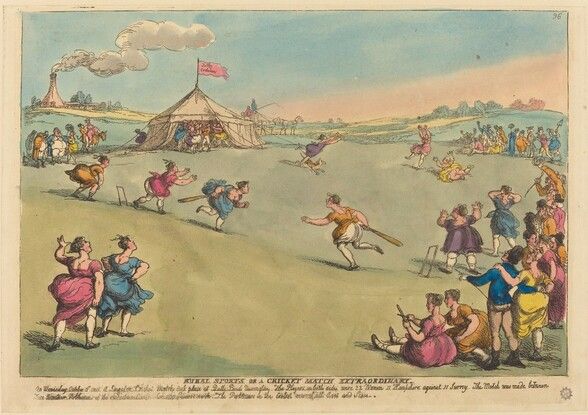

In 1811 a women’s cricket match took place at in Clapham. This was made famous by the publication of Thomas Rowland’s ‘Cricket Match Extraordinary’ picture published in Pierce Egan’s Book of Sports (see below). Billed as the first women’s ‘county match’, two amateur noblemen organised the game between their respective counties, Hampshire and Surrey, for 500 guineas a side. The noblemen paid to transport the women to London in carriages and arranged temporary residence at the Angel Inn, Islington.

Poster advertising the great game. Maria Coote is presumably the same as Mary Coote, referred to as one of “the two most famous Women in the Kingdom”. Sarah Chase, another cricketer was the other.

However – a point made by John Gloustone in his book, Hambledon, The Men and the Myths, is that most matches were advertised as being for 500 Guineas even when this was widely improbable. Indeed his researches have found several instances where the actual prize was only a tenth of what was advertised to the public. So the poster is less than reliable!

Rural Sports or a Cricket Match Extraordinary Hampshire v Surrey – Thomas Rowlandson – 1811. The illustration has much of the bawdy caricature about it and some have compared it to a brothel scene. You can however see the commitment of the players to the game – this is a match being played in earnest. I do wonder though, what is that brick kiln doing in the background, is there a double meaning going on there? Note also the two-stump wicket as well, which had started to be phased out in 1775, over 35 years previously.

Another illustration of the same match. Now with a three stump wicket. A short pitch though.

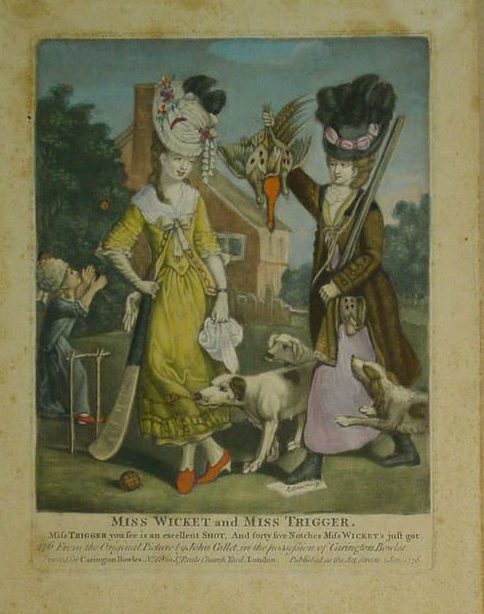

Miss Wicket

A print from 1778. The caption says “Miss Wicket and Miss Trigger. Miss Trigger you see is an excellent shot, And forty five notches Miss Wicket’s just got.” Miss Trigger is standing of a piece of paper on which the word effeminacy is clearly written. Is this being critical or expressing support? Certainly the ladies seem in fine spirits.

Miss Wicket meanwhile has been suggested to be the Countess of Derby (see above). Note the two stump wicket, although to be fair, the third stump only started to be used in 1776.

These two illustrations are apparently from tickets to matches, I am afraid I know nothing more. In particular, I wish I knew what the Ladies Cricket Club was or where it was based. I see that the lady is a rip-off from the Miss Wicket picture and the two stump wicket has been retained. On the right, by 1787, it has been changed.

Round-arm bowling and Christiana Willes

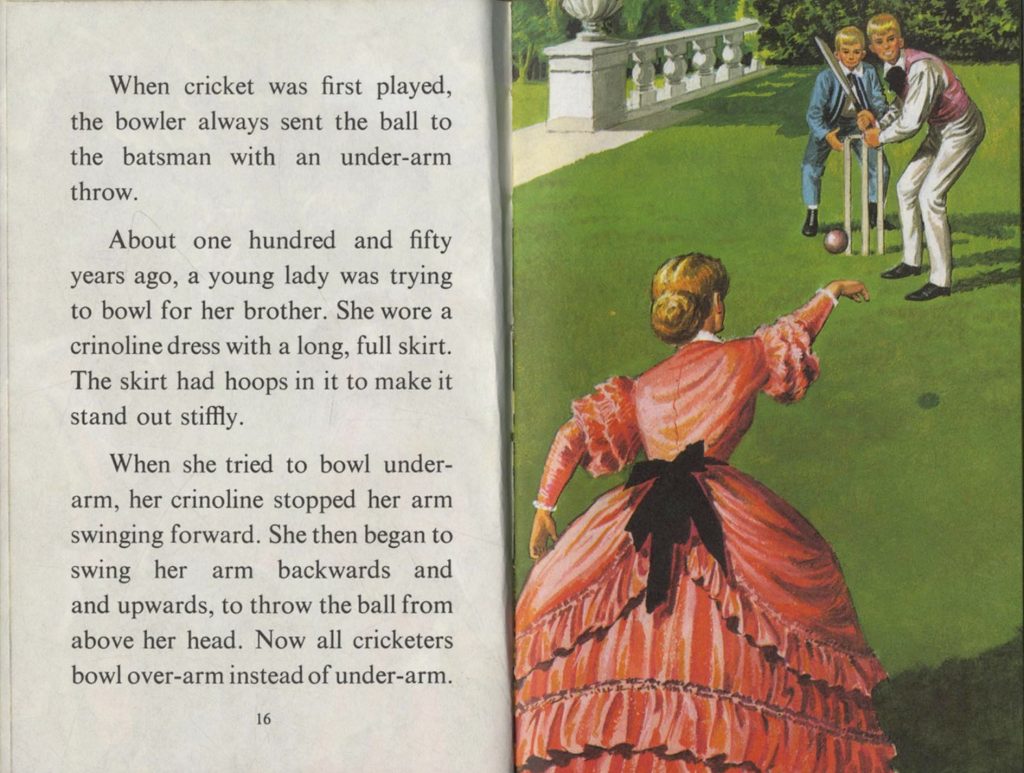

Another matter I would like to consider is round-arm bowling, often described as a female invention. The instigation of round-arm bowling lies beyond the time border of this website, but it is such an important matter and so often repeated, that it is impossible to resist considering it. The story, in its commonly accepted form, is told in the Ladybird Story of Cricket.

So is this story true? Well there are some difficulties:

- The first point to make is that this story is really about round-arm bowling (not overarm), where the arm comes through at shoulder height (a little like the brilliant former Sri Lankan fast bowler Lasith Malinga).

- The second point is that round-arm bowling was first tried by Tom Walker of Hambledon in the 1790s, frowned on and abandoned without being formally outlawed. The instance described here occurred in 1806, so it wasn’t fully an innovation.

- The third point is that the crinoline dress part of the story is not plausible – women weren’t wearing hooped crinoline in the early years of the nineteenth century. Also, it is not referred to in source material, it is clearly a modern embellishment.

Notwithstanding these points, the core of the story still contains a great deal that is possibly true. Christiana Willes (later Hodges) was the supposed bowler and the player who did most promote round-arm bowling in the elite game was definitely her brother, John Willes. The source of this story is Christiana’ son, John’s nephew, Richard, who, in his old age, recounted it in a letter. He said that his mother inspired John to try round-arm bowling by using this technique when they practiced together and, as noted above, did not mention the crinoline dress. Not everyone accepts the story, Rowland Bowen for instance regards it as fanciful. Meanwhile others tell a similar story but with a different player / sister combination. William Lambert is one player who had been mentioned in this context George Knight another.

Whatever the truth of that, it was from 1807 onwards that John Willes himself began to use round-arm from time-to-time, bringing his arm through at shoulder height. The technique was controversial and was formally outlawed in 1816 – the laws were changed to say that the bowling hand had to be below the elbow at the moment of delivery. Willes however, continued to bowl round-arm when the mood took him and, in a 1822 game, this resulted his him being continuously no-balled and his walking off the field in mid-match, and riding away, never to play again.

The controversy continued though, with bowlers gradually winning the argument. While the prohibition was formalised in 1828 (the hand could be at elbow height), it was relaxed in 1835 (the hand could be shoulder height) before being fully removed in 1864 – when overarm bowling was given license to became the norm. This is often identified as the birth of modern cricket.

Underarm still persisted for many decades with the last first-class practitioner, George Simpson-Hayward (23 wickets from 5 Tests at 18.3) played his last game for Worcestershire in 1914.

I still have more to say though. My father, born 1927, died 2020, late in life could still recall seeing one underarm bowler in action at a decent level. The player was Billy Hollies, father of the England leg spinner Eric Hollies. Eric was born 1912, so Billy was probably born around 1890 or earlier. The time my father recalled was around 1940 when Billy was at least 50. He was playing in Division 2 of the famous Birmingham League, for the great club, Old Hill. Dad recalled one season when Hollies senior got 94 wickets, mostly through prodigious spin. One of Old Hill’s former players, Ron Dovey, club captain for many years, played with Billy Hollies and died in 2024, aged 104. Perhaps the last tenuous link with an era of cricket whose end may well have been initiated by the actions of a young lady, over two hundred years ago.